After surviving the streets of post-war Korea, Thomas Park Clement was adopted by a loving family. Today, he’s honored around the world.

By his late 40s, Thomas Park Clement was, inarguably, a huge success. As founder and CEO of an established medical device company, he had touched the lives of millions of people. He held 24 U.S. medical patents (now 32), three college degrees, and an appointment to the Advisory Committee on Unification by the South Korean president. He was also a happily married father of two, a trapeze artist and a Tai Kwon Do expert.

No longer was he a “vulnerable tuki” – a half-Korean, half-Caucasian boy, surviving on the streets of Seoul at 5-years-old.

But once, on a humanitarian mission to North Korea, he glimpsed this younger version of himself.

“We were going to dinner, and right next to the front door was a 5-year-old orphan kid. He had no shoes and no socks,” says Thomas. “I thought, ‘that is my protégé.’”

How, he wondered, did I go from where he is to where I am now – training surgeons at the Ministry of Health?

“It was all through adoption,” he says.

Thomas Park Clement was born in war-torn South Korea – his mother Korean, his father an American GI. For the first four or five years of his life, his mother kept him in her care. Then, one day, she buttoned his coat tight and walked him into the busy streets of Seoul. She hugged him and kissed him and told him not to turn around. When he finally looked back, she was gone.

The first family to adopt him was a gang of street kids. Outsiders themselves, they overlooked what, at that time, Korean society could not. “In spite of the fact that I was obviously a biracial ‘tuki’ and they were pure Korean, they adopted me,” Thomas writes in his memoir, The Unforgotten War. Tuki, in Korean, means “foreign devil.”

“As a child in Korea I learned to think of myself literally as a devil … I was taboo,” Thomas writes.

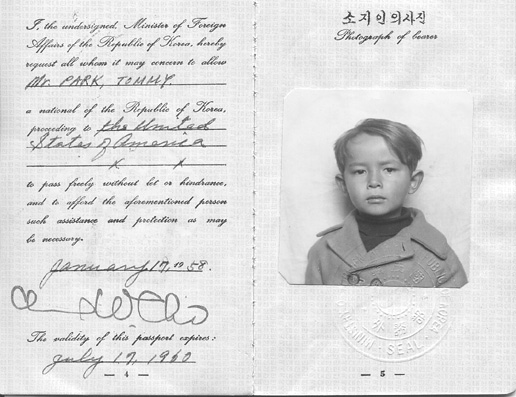

Thomas survived on the streets until, one day, a Methodist missionary took him to a local orphanage. In 1958, June and Richard Clement adopted Thomas and brought him home to the U.S.

Overnight, his life upturned.

It was “Christmas every day.” Not only did he have his own bed, but his own room. He learned the meaning of “seconds” at mealtime, and that rainy days meant bicycling in the garage. Overnight, he had a mother, a father, a sister and a brother. He had an Aunt Edie, Aunt Nettie and a grandma. Overnight, he had a family.

As a small boy in a foreign place, he had many fears as well. The TV shootouts between cowboys and Indians were all too real for Thomas. Often, he woke up screaming from nightmares about the war – a war he could not, and never would, forget.

But nothing in his new world scared him as much as the prospect of returning to the old one. “I did not want to go back to the orphanage,” he writes. “I did not want to go back to the war.”

Breaking the Silence

Thomas eventually overcame his childhood fears. But although he had love and security and more food than he could ever eat, secretly, something was always missing – a “sadness” in his heart. He never voiced these feelings – not with his family, not with his friends. Older generations of adoptees share a common understanding that “you did not talk about adoption in the family,” he says. This left many feeling voiceless, in “silent conversation.”

Not until his 40s did Thomas find his voice – after typing “Korean adoptee” into a search engine.

“It was the most incredible feeling in the world,” he writes. “After 40 years of being in the United States it occurred to me that I hadn’t ever known or seen or met another KAA.”

He discovered a huge, vibrant community of international adoptees, living all over the world. By “surfacing” in this community, he could share the feelings he thought no one else could understand. “That’s the coolest thing about adoptee gatherings,” he says, “the commonality.”

After breaking the silence, Thomas found he had much more to say. He began writing. “That was one of the biggest motivations,” Thomas says of his memoir. “We have a voice, and we can talk about it – about adoption.”

Thomas’ voice proved powerful. The Unforgotten War sold over 20,000 copies. “Some of them said it sounded like I was talking directly to them,” he says of his fellow adoptees.

In many ways, he was. After surfacing in the community, Thomas began counseling adoptees and their families. During 3 a.m. phone calls, they shared their frustrations and fears, their feelings of alienation, encounters with prejudice. In many passages of his book, he directly addresses the issues he’s helped adoptees work through over the years. He emphasizes the importance of connecting with other adoptees, and explains how he copes himself.

Feeding the Fire

Thomas considers himself a “testimonial of the positive outcome of adoption.” Of his success, he writes, “the most important influence was the love and support I received from my adoptive parents and family.” He also recognizes the complexities, and imperfections, of international adoption. Fellow adoptees have asked how he can be so positive – how, having endured so much hardship, having been called “‘roundeye’ in Korea and ‘slanteye’ in America,” he is not bitter.

For this, he also credits his family – his birth mother, who cared for him during the critical first years of his life, giving him an “essential confidence in people,” and his adoptive parents. “If I think about the Korean War, living on the streets and the orphanage, I could be ‘totaled’ by these thoughts,” Thomas writes. “Or I can use these life experiences to feed the fire…to make the world a better place for our children in the future. This attitude I owe to my parents.”

Thomas supports humanitarian efforts in Africa and North Korea – where, in recent years, he helped build a research center for drug-resistant TB. Through an organization called First Steps, he also supplies food for children living in the country’s orphanages. For children like his “protégé.” Children, once, just like him.

Robin Munro | Content Manager

Over the years, many more adult adoptees have broken the silence. In April, adoptees from around the world gathered in Washington D.C. to celebrate and reflect on 55 years of international adoption. On the opening day of this international forum, eight adoptees shared their stories at the National Press Club. Click here to listen.

born in seoul aug 1952 adopted from catholic charities orphanage seoul brought to detroit michigan may 1956 at 4 y/o by marvelous people mary and phillip lee changed name from syung won kim to wayne kim lee now live in st augustine florida brought here by joining the USN and staying/learning/working/loving in florida.

great statement about KAA’s glad to know about thomas

I’ve known Tom for nearly 40 years, and he is a great friend and even better person. For many years I had no idea he was adopted nor Korean. I simply knew him as a best friend. I am better for knowing him.

I, too, did not know about connecting with Korean adoptees until I did my own search in my early forties. I finally went to Korea on a scholarship offered by GOAL in Korea for first timers going to Korea. I still do not know who my birth parents are, but it did soothe a bit of that ‘heartache’ or ‘longing’ I felt all my life but not knowing exactly why. I plan to go to Korea and live there for about a year or so teaching English and in hopes to ‘maybe’ find a bit more about my parents and volunteer at a local orphanage to give back as much as I can of what I was given…a second chance in life. I am forever grateful to my American parents!

Geez you guys…. read this whole thing and couldn’t help but cry…. life has been so utterly strange…. and unbelievable… but the bottom line is this… no matter what the atmospheric turmoil of the day is…. the underlying message is….. it’s the goodness within our hearts that will prevail over all else….

My adoptive parents did all they could to teach me Korean culture, taking me to Korean adoptee groups and Korean culture camps in my childhood years. Through interactions I’ve had with other Korean friends, I‘ve been told repeatedly I don’t look 100% Korean with certain physical features such as “bigger eyes” and having “eye-folds”. I have often felt alone and confused.

Now in my late 30’s, my sweet husband did some research on DNA testing and types of databases. I’m renewed with some hope in the slight possibility of finding my birth parents or other family members through your DNA-testing. I just ordered a kit last night. Perhaps the returned results will yield some insight into who I am.

Thank you Thomas Park Clement for using your talent, time and means to provide this resource, using your platform to speak-up for the good of other fellow Korean adoptees. I pray this is a catalyst to reunite many that have felt lost in finding loved ones. We need more of this good-will in our world!

#koreanadoptee

#koreanbirthmother