One boy’s story of life in a Cambodian orphanage, and how Holt sponsors and donors helped him come back home to his family.

When Kea lived in the orphanage, he slept on the bottom bunk in a room full of bunkbeds occupied by teenage boys who left him out of things and made him feel alone.

“I was the smallest,” he says. “That’s why I didn’t have many friends.”

In the morning, if he slept too late, the orphanage cook would throw water on him to wake him up. He would help clean the pigpen, eat a breakfast mostly made of rice and go to school. After school, he had to come straight back to the orphanage. He did his homework by himself. He ate more rice. And went to bed.

“No one took care of me,” he says.

When Kea was 6, he caught a fever. He remembers it felt “like a shock,” he says, “very cold, but inside, very hot.” After the shock, he would never walk the same. His legs bowed inward and he could no longer stand up straight. His caregivers didn’t take him to the hospital until after his fever broke and his legs had collapsed inward at the knees. His caregivers told the doctors that Kea played too much soccer. But even at 6, he knew that was not the truth. Most likely, it was polio, not soccer, that left him permanently disabled.

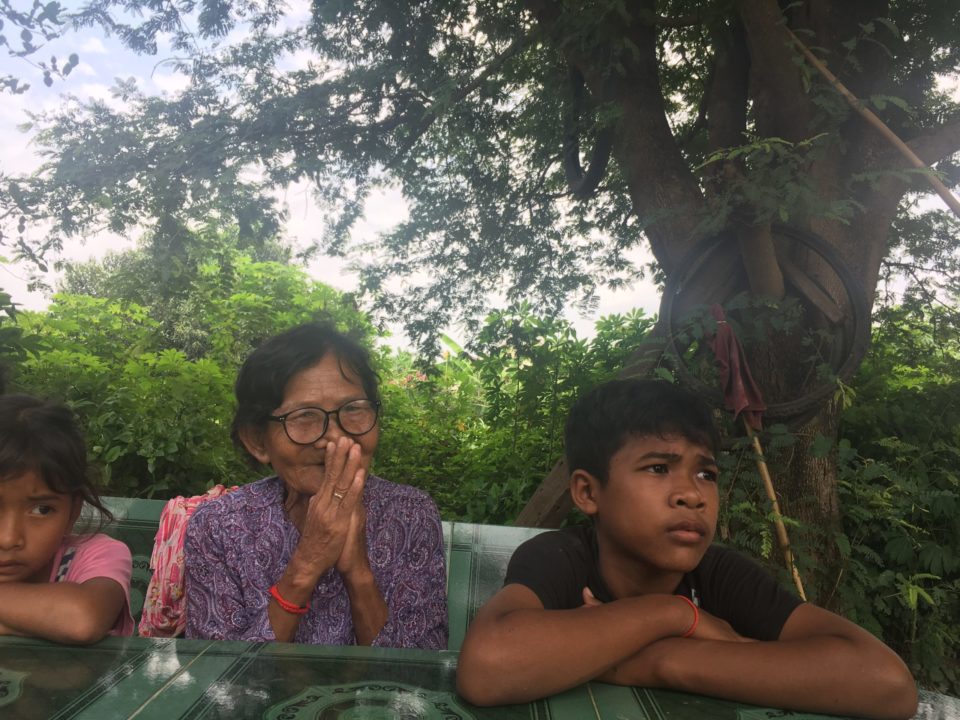

We meet Kea on our last day in Cambodia. It’s late September, warm and muggy, and he tells us his story as we sit outside under the shade of a tree. Kea is now 12, and lives with his grandma and two younger sisters. He is shy and soft-spoken, with a sweet, gentle nature and kind, sensitive eyes. He sits quietly with his chin resting on his arms as adults talk around him. His grandma is quite elderly and hunched, with large, round, black-rimmed glasses and a kind, toothless smile. She takes off her glasses and quietly wipes tears on the sleeve of her shirt as she shares the reasons why she placed Kea in an orphanage nine years ago, when he was only 3.

“I’m just very sorry,” she says. “I decided to place him in the orphanage because at the time, I looked after five children alone. I didn’t have any job to make money.”

“I’m just very sorry. I decided to place him in the orphanage because at the time, I looked after five children alone. I didn’t have any job to make money.”

Kea’s grandma

Their family lived in extreme poverty, and the only way to earn a real income was to leave. Kea’s father left first, and eventually, his mom also left to find work in the city — leaving Kea and his two younger sisters in their grandmother’s care. At the time, Kea’s grandma was also caring for three more of her grandchildren. All of their parents had migrated away from their rural province to try to find work in Phnom Penh or another big city.

Caring for five young children on her own, including two infant girls, Kea’s grandma felt like she had no choice but to place her grandson in the orphanage. “I didn’t have any money so I couldn’t afford food,” she says. At least in the orphanage, she thought, Kea would have food. He would be able to get an education.

“I thought, one day, I would bring him back when I have the ability,” she says. Nine years went by. All that time, Kea stayed in the orphanage, only coming home for holidays. His parents never came to see him.

Then, one day, a Holt Cambodia social worker came to visit Kea’s grandma and ask her how she would feel about her grandson coming home to live with her.

A Legacy of Uniting Children With Families

In 1955, Harry Holt was just a farmer when he traveled to Korea to help children left orphaned and abandoned in the wake of the Korean War. He didn’t have a master’s degree in social work. Even among scholars, little was known in the 1950s about the emotional and cognitive deficits caused by long-term institutionalization. But intuitively, Harry knew that children needed more than just food, shelter and education to grow into thriving, healthy adults. They needed the love and stability and total devotion of a family.

Over the past six decades, Holt International has allied with countries around the world to help move children from orphanages into permanent, loving families or more nurturing, family-like settings.

Over the past six decades, Holt International has allied with countries around the world to help move children from orphanages into permanent, loving families or more nurturing, family-like settings.

After the Ceausescu regime collapsed in Romania in 1989, Holt was among the first organizations to come to the aid of the more than 100,000 children found to be living in horrifying conditions in the country’s state orphanages. Born out of the regime’s brutal workforce-growth scheme in which women were denied birth control and faced stiff fines for childlessness, the children living in these state orphanages mostly came from poor families who ended up with more children than they could support. Holt trained local staff to investigate the children’s backgrounds and helped reunite many of these children with their birth families or placed them with adoptive families in Romania or the U.S.

In the early 1990s, in China, Holt was also among the first agencies granted permission to help find adoptive families for the thousands of children, mostly girls, whose parents felt they had no choice but to abandon them lest they face the consequences of breaking the country’s one-child policy.

Today, Holt continues to pioneer efforts around the world to help children grow up in families, not orphanages. And of anywhere in the world, Cambodia is currently among the countries with the highest rates of children living in orphanages who could be living with their families.

Four years ago, with grant funding from the GHR Foundation, Holt launched a pilot program in Cambodia to help children like Kea go back home.

Why Kids Grow Up In Orphanages

Cambodia’s orphanages are diverse in many ways. Some are privately funded. Some are government-run. Some are smaller, group home-like settings, like Kea’s, where mostly older children live side by side with the elderly and disabled adults. Others are crowded with young children and not nearly enough caregivers to take care of them.

But across Cambodia, all orphanages have one heartbreaking thing in common — the vast majority of the children in care are not, in fact, orphans. They have families. Most of them have living parents. And almost all of them have someone — a grandma, an aunt, an uncle, an older sibling or cousin — who they could live with.

But because so many families in Cambodia live in poverty, few can afford to take in a relative without some kind of assistance.

Thoa Bui is Holt’s vice president of international programs. She has worked for Holt for 11 years, seven of them at the Holt office in her native Vietnam, and currently oversees seven of Holt’s 14 country programs, including all of Holt’s programs in S.E. Asia. She first traveled to Cambodia in 2013. “When I first got to Cambodia, I was shocked,” she says. “I was thinking, ‘This is the worst I have ever seen in terms of poverty.’”

“When I first got to Cambodia, I was shocked. I was thinking, ‘This is the worst I have ever seen in terms of poverty.’”

Thoa Bui, Holt’s vice president of international programs

Cambodia has two classifications for poverty — “Poor Two” and “Poor One.” “Poor Two” families live in poverty, but they typically have at least a radio and a TV, maybe a motorbike, our in-country staff says. “Poor One” families have basically nothing. They can barely afford food, much less the costs of a basic education. They are Kea’s family.

In rural Cambodia, especially, families struggle to survive on what little their land can produce. Increasingly long periods of drought and occasional floods have led to significantly reduced yields of rice and other staple foods.

“People living in rural Cambodia, they really don’t have jobs,” Thoa explains. “They don’t have enough water. It’s hard to grow anything or do anything to really earn any income there … People have to really focus on survival.”

In recent years, more and more young people have begun migrating internally to cities within Cambodia or even over the border into Thailand or other countries to find some kind of work — anything to help their families survive. When families migrate, children either travel with their families, or stay behind in the care of elderly relatives.

“Or the parents migrate for work and there’s no one left to care for the children,” Thoa says. “Then, the parents think it’s better for the children to be in the orphanage.”

Of course, it’s not better for children to grow up without their family. In the 64 years since Harry Holt intuitively recognized the vital importance of a stable, loving family to a child’s overall health and wellbeing, developmental psychologists have well documented the long-term, detrimental effects of growing up in institutional care. Many of these studies were, in fact, conducted on the children who grew up in Romania’s state orphanages during the Ceausescu regime.

But whether in Romania or China or Cambodia, when families can’t afford food for their children, the intangible things that parents give their children — like time and attention and love and affection — become luxuries. Survival comes first.

“We cannot blame these parents,” says Thoa. “It’s just the reality. Because we’re talking about survival … But that’s the thing children miss all this time — the love from their parents, the connection.”

The Importance of Sponsors

For that, Holt Cambodia would need to rely not just on the grant funding they received to launch the program. They would need the help of individual donors — of monthly child sponsors.

When Holt first began working alongside the Cambodian government to address the crisis of children growing up in orphanages, our local staff recognized that it would take more than just tracking down relatives for children to successfully reunite with their families. Of course, locating family members of children who’ve spent years of their life in an orphanage was already a monumental feat. But once they did find their families, our staff had to communicate why it’s so important for children to grow up with the love and connection that only families can give them — even if it means going without the free food and education the orphanage provides. And they had to make sure the families had the resources to care for them. That they would survive.

“We started to think about the sustainability of the program after GHR funding ended,” says Thoa. “We enrolled 90 children into Holt sponsorship and began assigning sponsors to the children. Sponsors support basic needs like education and income-generating support for parents, emergency support for hungry families, which is a huge help.”

“Sponsors support basic needs like education and income-generating support for parents, emergency support for hungry families, which is a huge help.”

Thoa Bui

Two years ago, when Holt’s local social workers approached Kea’s grandma about bringing him home to live with her, she wanted to say yes. But she didn’t know how she would care for him. She still had two of her grandchildren in her care, and also cared for one of her adult sons, who had a mental disability. One of her grown daughters also lived with her, and brought in some income — but not enough.

“I understand the importance of children living in a family so I was very happy to welcome him back home,” she says. “It didn’t mean I have the ability to raise him, but I didn’t want him to live apart from me anymore.”

Working with the local government, Holt social workers made a plan for this family. Through the generous support of sponsors and donors, they would provide food and school supplies and help renovate their home, which was in dangerous disrepair. They would provide ongoing counseling to help Kea transition back into life in a family, which would be dramatically different from his life in the orphanage. And they would help Kea’s family develop a long-term plan to generate income — and ensure both Kea and his sisters stayed in school through 12th grade.

Two years later, as he sits under the tree outside his grandma’s house, Kea says he is so happy to be back home. He looks down, a big smile on his face.

“I really like living with my grandma because living in the orphanage was very hard,” he says. In the orphanage, he had to work all the time and had no freedom. Now, he spends his afternoons playing with his sisters or riding around the village on the bike that a Holt donor gave him as a Gift of Hope — making it easier for him to get to and from school. He has more to eat than just rice. No one throws water on him in the morning anymore. And most of all, he no longer feels alone.

“How do you think your life would be different if you stayed in the orphanage until you turned 18?” we ask him.

“I would be lonely because there are no other kids my age in the orphanage,” he says. “I would feel lonely, and I think I might be alone forever.”

“I would be lonely because there are no other kids my age in the orphanage. I would feel lonely, and I think I might be alone forever.”

Kea

Asked what he would like to say to the people who helped him move back home, he smiles — too shy to look directly at the camera — and says, “Thank you very much for helping me to live with my family.”

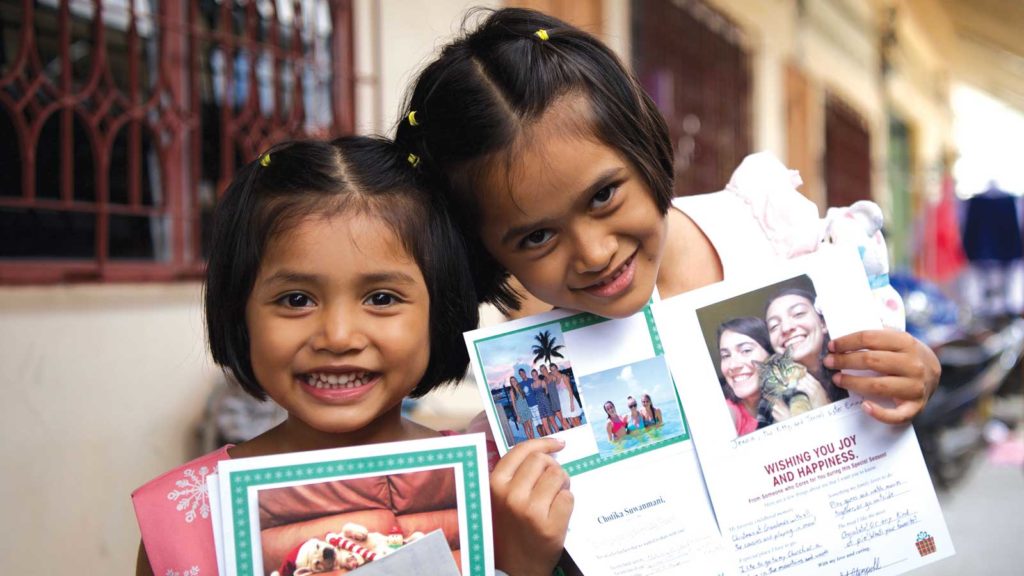

Become a Child Sponsor

Connect with a child. Provide for their needs. Share your heart for $43 per month.