Families living without safe shelter face all kinds of threats — especially during the rainy season in Cambodia. Ten-year-old Linna lives in the city. Eleven-year-old Thak Kan lives in a more rural area. Neither of them have a safe place to live.

Thak Kan sits between his parents as his mom wipes tears from her eyes and his dad holds his little sister in his lap. His little brother sits on the other side of his mom. Thak Kan looks down, his brow knit tightly together. Sleepy, he rests his head on his dad’s shoulder. He is 11, but looks small for his age.

“How do you feel when it rains really hard?”

“Scared,” he says. His voice is sweet, soft and high.

Thak Kan lives with his parents and three siblings in a rural community just outside of Battambang, a city in northwestern Cambodia. It’s the middle of the rainy season when we visit them, and the unpaved roads to their house are slick with fresh mud. As we get closer, Thak’s dad, Bunthong, reaches out to give us a hand maneuvering around the mud puddles. A murky brown pool of ankle-deep water surrounds a little shack that sits to the left of their house. That’s their bathroom.

Their house sits on higher ground. But unlike most houses in rural Cambodia, which are built on tall stilts, their house is still on the ground — leaving them vulnerable to flooding, and to all the creatures that seek dry shelter when it rains.

“Two times, a snake came into our house,” Thak’s mom, Kola, says — crying and talking fast in a trembling voice. “Most of the snakes are poisonous. So we’re afraid.”

“Two times, a snake came into our house. Most of the snakes are poisonous. So we’re afraid.”

Kola can’t sleep well when it rains. She leaves the lights on all night, and watches the holes in the floor and the walls. The whole family sleeps together on a woven floor mat — under a single mosquito net. They are scared of snakes, and of scorpions, which also live in the jungle surrounding their home.

Kola seems exhausted with worry, and exhausted with caring for four children— including a 3-year-old daughter who sways in a nearby hammock as we talk. Kola is only 31 years old. Her husband is 34. They are a beautiful couple, with beautiful children. But they are struggling to survive.

Even when it’s dry, Kola gets almost no sleep these days. To help support her family, she gets up in the middle of the night to make cakes, which she then sells in the marketplace in the afternoon.

“I have to get up at 3 in the morning. If I can’t get up on time, I can’t sell the cakes,” she says.

Thak’s father, Bunthong, works as a day laborer at a construction site, but his work is unstable and he earns very little. Together, Thak’s parents earn about $5 a day. Neither of them have much education. They both grew up in poverty and dropped out early to help their families earn a living. Bunthong finished seventh grade. Kola made it through the third grade.

“I want my children to study to grade 12,” Bunthong says, softly like his son. “I don’t want our children to be like us.”

With limited opportunities in Battambang, many people in this community migrate to the Thai-Cambodia border to find work. It can be a treacherous journey, especially if they cross the river into Thailand, and they often leave their children in the care of grandparents or family members. But Kola and Bunthong’s youngest child is still very small, and they don’t want to leave her. She would have to come with them, which would be dangerous.

To provide better for his family — and stay together in one place — Bunthong would like help starting a small business. A food cart that he could run himself so that he can earn money every day — not just on the days he can find work.

But their first priority, he says, is a proper house. A house built on tall stilts to protect them from flooding, with a solid roof and walls.

A new house would keep out snakes and scorpions. It would also help protect them from the mosquitos that harvest their eggs in the stagnant pool of water that surrounds their outhouse. Where they live, mosquitos carry both malaria and dengue fever. And more than once, their children have fallen sick with dengue, which causes high fever, pain, even bleeding — and grows more serious the more times you have it. Each time their children have gotten sick, Kola and Bunthong have had to borrow money at a high interest rate to pay the medical costs — driving them into debt.

Kola also has persistent stomach problems. But she never gives up. Every night, at 3 a.m., she wakes up to make cakes. Otherwise, her family won’t eat.

Seeing where they live, hearing their story, it’s so obvious how poverty cycles from one generation to the next. Thak’s parents grew up poor, and didn’t receive an education because their families needed help earning money, and couldn’t afford the cost of fees, books and supplies. They married young — at 19 and 23 — and had child after child because they didn’t have access to family planning services. They didn’t have any real opportunity to earn a stable income, no matter how hard they tried. They got sick, and got into debt.

But they are determined to break the cycle. To keep their kids in school. To help their kids live a different life.

“I always encourage my kids to study hard because if they’re not educated, like me, it’s very difficult,” Kola says.

“I always encourage my kids to study hard because if they’re not educated, like me, it’s very difficult.”

Right now, they barely scrape together the money to pay their kids’ school fees. But they worry they won’t have the money to keep all of them in school. If one of their children gets sick again, they will have no choice but to go deeper into debt. If that happens, Thak Kan or one of his younger siblings may have to drop out.

They live in a constant state of risk. But the greatest risk — the most immediate and the most deadly — lives in the trees and brush around their house. It’s only a matter of time before one of them gets bit.

“We always worry about our kids,” Bunthong says. Kola wipes tears from her eyes, and braves a smile. Thak Kan looks down, his brow knit together in an expression far too serious for an 11-year-old.

———

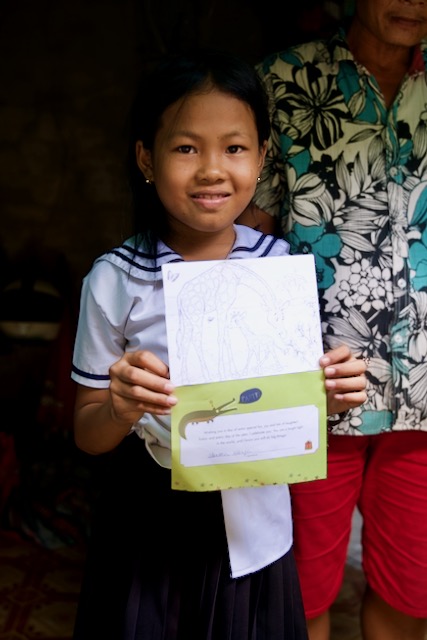

Linna lives with her mom, dad and older brother in a slum community of Phnom Penh. She just turned 10, and is about to start fifth grade. It’s a sunny September morning when we stop by her house for an interview. She’s washing dishes in a big metal pot on a wooden table out front, still wearing the white button-down sailor shirt and long blue pleated skirt of her school uniform.

Her mom works in a garment factory. Her dad had a good job as a security guard, but now works as a fisherman. It’s just Linna and her dad at home this morning.

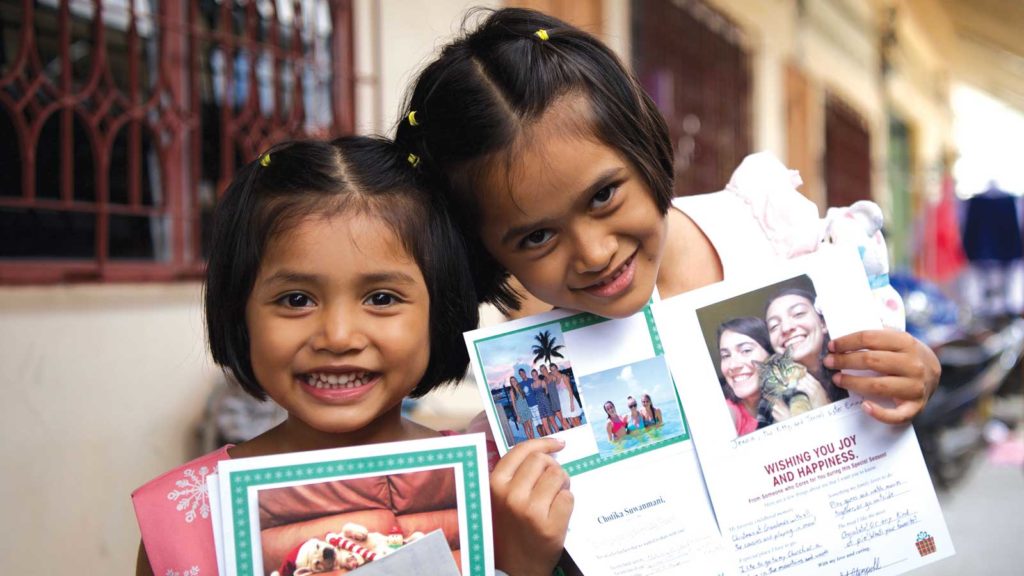

We ask Linna about school, her life, what she likes to do, what she wants to be. Linna has a Holt sponsor who helps pay the monthly fees for her to attend school, and both she and her father share how thankful they are for the kind and generous support of this wonderful person they’ve never met. Linna shows us a birthday card she received from her sponsor, and tells us that sometimes, she writes letters in response — to say thank you. She tells us that she loves math and Khmer literature, and loves playing a game with her friends where they write letters in the sand.

“I want to be a teacher,” she says. “But if that’s not possible, I want to work in a beauty salon.”

Although Linna is among the top students in her class, she knows that her opportunities will be limited if she doesn’t graduate. She also knows that where she lives, going to school is a privilege — not a right.

“Before Linna had a sponsor, my children sometimes could not go to school because I had no money for them,” Linna’s dad tells us. “We lied to the teacher and said, ‘Oh, my children are sick.’ They would stay home. Sometimes, they would help me fish.”

If not for her sponsor’s help covering the cost of fees, uniforms, books and supplies, Linna would have to drop out of school, he says. He would also struggle to provide enough food.

“The sponsor helps my daughter a lot,” he says. “[Her sponsor is the] reason I can afford three meals a day for my daughter.” Before, when he couldn’t afford food, he would borrow from the neighbors, and pay them back when he earned enough.

“The sponsor helps my daughter a lot. [Her sponsor is the] reason I can afford three meals a day for my daughter.”

Linna sits quietly by her dad as he talks, playing with a ring on her finger. Her shoulders are a bit hunched, but she smiles brightly when we ask her questions.

“Is there anything you’d like your sponsor to know?” we ask her.

“Yes,” she says, in a very soft voice. “I want to share that before, I used to miss school a lot and I didn’t care about the schoolwork. But after I got the support from my sponsor, I began to study harder. I memorized the lessons at home and I read the lessons … Now I’m number 4 in the class!”

Just as we’re about done with our interview, the winds pick up and the sky starts to cloud over. A few drops of rain start to fall. Linna knows what to do. She starts walking around her house, moving inside anything that needs to stay dry and placing big plastic buckets in strategic spots around her home.

Her house has no walls or doors, and no real roof — just a series of tarps layered over metal slats to form a makeshift shelter. Her house also has no rooms or floor — just a series of raised wooden platforms set against a cement wall, and separated into partitions by sheets. Electric wires hang every which way, plugging into a single wall outlet. Linna, her brother and her parents sleep under a mosquito net on one of the platforms. They don’t own their land, but are allowed to live here as caretakers.

Like many families in this community, Linna’s family migrated to Phnom Penh because they believed they would have better opportunities than in their home province — a rural area like where Thak Kan and his family live.

The garment factories just outside the city pay relatively well, Kosal Cheam, director of Holt Cambodia, explains.

“But land and homes are very expensive in Phnom Penh,” she says. “Jobs are temporary. Housing is temporary.” And quite often, our support is temporary, too, because families often migrate again — leaving the area, and our sponsorship program.

But Linna’s parents are determined to keep their children in school. And if they stay in this community, Linna can also stay in Holt sponsorship.

“If she could get a high education and then get a good job, her life will be better than my life today,” her dad says. “She could own a house — not like me, I own nothing. I don’t own a house so whenever our landlord tells us to leave, we have to move.”

Just as we’re about to leave, the rain starts to pour. And hard. We barely have room to crowd under Linna’s roof. Water runs as though from a bath tub spout on full blast — making a sound like white noise, broken up by grumbles of thunder. Linna, still in her school uniform, gets soaked as she hurries from one place to the next — moving buckets that fill too quickly for her to keep up. The ground, moments ago so hard and dry, turns to mud that squishes between her toes as she runs around in bare feet.

She smiles, wipes the water from her forehead and scrunches up her shoulders, as if to say, “That’s the best we can do!”

Linna says it’s hard to sleep when it rains at night. She has to move around a lot to avoid getting wet from water dripping through the roof. She still gets up the next day and goes to school. But she’s tired, and tries to nap during breaks.

After a while, Linna just sits down on the edge of the platform and waits for the rainstorm to pass. This happens almost every day during the monsoon rains. In Cambodia, the rainy season lasts from May to October.

Become a Child Sponsor

Connect with a child. Provide for their needs. Share your heart for $43 per month.